This blog is about the German Tax Office and is therefore in German. If you aren’t German, you probably wouldn’t believe that an organisation could be this disorganized anyway.

Vor ein paar Jahren war ich zu einem Treffen zwischen dem Finanzamt und den örtlichen Steuerberatern in unserem Teil Deutschlands eingeladen. Der Chef des örtlichen Finanzamtes stand stolz auf und prahlte damit, dass er eines der professionellsten und modernsten Ämter in Deutschland führe. Niemand lachte, aber niemand glaubte ihm.

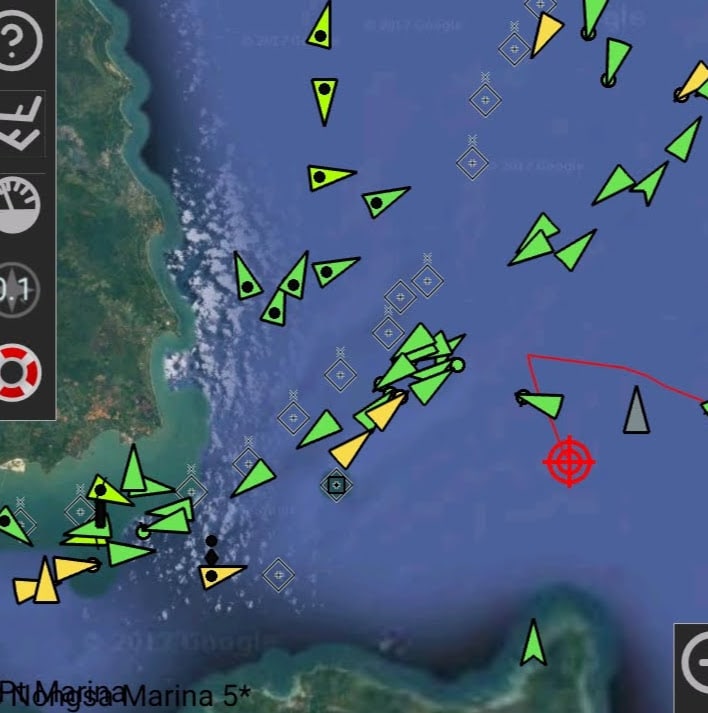

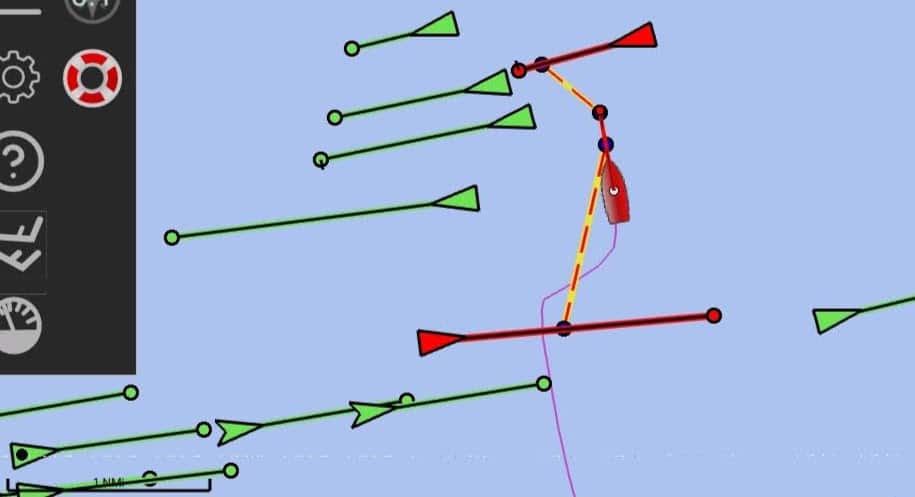

Als Segler haben wir fast Alle, mit denen wir zu tun haben, erfolgreich auf “digitale Kommunikation” umgestellt. Meistens war es einfach, aber das Finanzamt hat gezeigt, wie schwierig eine Organisation es machen kann, wenn sie es wirklich versucht.

Das Finanzamt schreibt überall im Internet darüber, wie erstaunlich digital sie sind und dass du dich nur für ihr digitales System “Elster” anmelden musst.

Um Elster zu nutzen, registrierst du dich zuerst online und bekommst dann eine E-Mail zugeschickt, um zu beweisen, dass du es wirklich bist, und dann schicken sie dir einen Brief per Post, um zu beweisen, dass du es wirklich, ehrlich, wahrhaftig bist. Du brauchst gute Nachbarn, wenn du mit dem Finanzamt digital werden willst. Zum Glück sind Andi & Iris Experten darin, unsere Briefe zu öffnen und uns ein Foto per WhatsApp zu schicken.

Als Nächstes erhältst du ein digitales Zertifikat, das du niemals verlieren solltest und mit dem du dich einloggen und unter anderem dem Finanzamt digitale Nachrichten schicken kannst. Du lehnst dich lächelnd zurück und denkst: “Ja! Das war einfach. Ich bin ein digitaler Held.”

Ein paar Tage später schrieb ich unsere erste vollständig digitale Nachricht und sie schickten mir eine Antwort – als Brief. Daraufhin schickte ich ihnen die Umsatzsteuer, die ich ihnen schuldete, und eine digitale Erklärung für die Umsatzsteuer. Sie beantworteten dies mit zwei Briefen. In dem einen stand: “Ich soll ihnen kein Geld schicken” und in dem anderen: “Wo ist das Geld?” Wenigstens haben Andi und Iris nicht vergessen, wie man Briefe fotografiert. Ich schrieb ihnen eine weitere digitale Nachricht: “Wie kann ich euch davon abhalten, mir Briefe zu schicken und euch dazu bringen, mir digital zu antworten?”

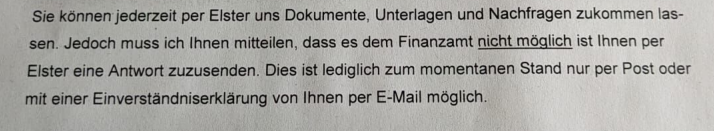

Ein weiterer Brief (warum bin ich nicht mehr überrascht), in dem steht, dass wir Elster zwar benutzen können, um ihnen zu schreiben, sie aber nicht digital über ihr eigenes System antworten werden, weil “es nicht möglich ist”. ABER, wenn wir ihnen ein vollständig und korrekt ausgefülltes Einwilligung in den Versand unverschlüsselter E-Mails durch Finanzbehörden gemäß § 87a Abs. 1 Satz 3 Halbsatz 2 der Abgabenordnung (AO) senden, dann würden sie mit Emails antworten. Das haben wir natürlich getan.

Diesen Monat habe ich meine Umsatzsteuer bezahlt und die Erklärung digital abgegeben. Als “Dankeschön” erhielt ich einen Brief, in dem ich gefragt wurde, warum ich Geld gezahlt hatte. Andi und Iris zückten ihre Kameras und schickten ein Foto nach Singapur und ich schickte eine weitere digitale Nachricht mit den Worten: “Was muss ich noch tun, damit ihr mir keine Briefe mehr schickt?” Heute erhielt ich eine Antwort …

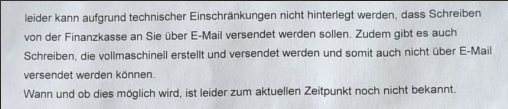

“Wir, das deutsche Finanzamt, sind nicht in der Lage, dir eine andere Antwort als einen Brief zu schicken. Wir haben keine Ahnung, ob und wann wir Sie jemals digital kontaktieren können.”

Das Schlimmste an all dem ist, dass die gesamte Organisation mit Steuern bezahlt wird. Wir brauchen keine höheren Steuern. Wir brauchen eine funktionierende Verwaltung.